Research

Our research focus for 2022/2023 is Generative AI.

Spring quarter of 2023 there was a Generative AI and Education seminar course hosted by HCI at Gates and led by Professor John Mitchell and Glenn Fajardo.

Every week a diverse group from around campus gathered to show off recent work around generative AI and discuss the connections with education.

One particularly interesting and fruitful area in and around campus included:

Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior

This paper introduces generative agents, computational software agents that simulate believable human behavior. The architecture extends a large language model to store and synthesize agents’ experiences, memories, and plans using natural language. These agents are instantiated in an interactive sandbox environment inspired by The Sims, where users can interact with them using natural language. In evaluations, generative agents demonstrate believable individual and emergent social behaviors. The paper shows that the components of the agent architecture — observation, planning, and reflection — are essential for believability. This work lays the foundation for simulations of human behavior by merging large language models with interactive agents.

You can read a more detailed breakdown of the paper here.

Our research focus for 2021/2022 was Playful Learning.

Project Zero and our friends at Harvard Graduate School of Education released a great book on playful learning called Pedagogy of Play. You can read Chris Bennett’s book notes here.

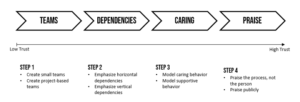

Our research focus for 2020/2021 was Trust. Chris Bennett and intern Shaan Asif published a white paper on designing for low-trust situations.

Organizational Trust-Building in Low-trust Nations: A Framework leverages qualitative interviews and existing research to examine the process of organizational trust in the context of Pakistan, one such low-trust nation.

Our research focus for 2019/2020 was the Neuroscience of Design.

Chris Bennett and Margarita Quihuis created two online courses for the Peace Innovation Network to discuss this subject:

- Lessons from Super Mario: Game Design Thinking (introductory course)

- Game Design Thinking (full course)

We delved into the Neuroscience of Design in these courses and discussed how to apply this science to products, services, and education.

Our research focus for 2018/2019 was Innovation Culture. This is an expansion of our work that we started last year around creativity and culture. How can Game Design Thinking help to create a culture of innovation that grows in a healthy way?

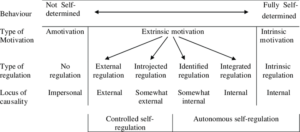

We study Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory, which shows motivation as more than just simply there or not there.

Deci and Ryan state that the three inherent drivers of motivation are:

- Competence

- Autonomy

- Relatedness

How can we find ways to utilize all three of these for important tasks in the experience we are creating?

And stepping back, how can we even see where a person is on this Motivation Chart above? What are the best assessments for testing this?

Our research focus for 2017/2018 was Creativity. How can Game Design Thinking inform how we foster creativity and innovative thinking in individuals and organizations?

Out of this research came The Innovation Equation. What components are necessary for a group of collaborators to encourage truly innovative thinking.

The Innovation Equation: Innovation = Friction + Inclusion + Trust (FIT)

Friction: In a process meeting, we need to get on the same page and reach consensus. To have truly innovative ideas, though, we need to disagree. Do we have processes in place so the group can disagree and debate in a meaningful and respectful way?

Inclusion: Do we have different voices in the room? Are those voices truly being heard, acknowledged and valued? Inclusion is the deliberate act of welcoming diversity and creating an environment where all different kinds of people can both succeed and thrive. Diversity is what you have in the room, but Inclusion is what you do with your voices.

Trust: Do we feel comfortable enough with this group to put our best work forward? Are we willing to take a chance of failing? Do we have the support of our collaborators? People take chances when they feel their collaborators have their back.

Our research focus for 2016/2017 was Neuroplasticity. How are our brains actually affected by what we experience? How can we design for better plasticity?

Margarita and Chris learned about the NIRS headset by participating in a study by the Center for Interdisciplinary Brain Sciences Research at Stanford University School of Medicine.

The post-docs running the study also shared more of their work around brain scanning and cooperative games.

The combined portability and power of NIRS (as compared to the non-portable fMRI or portable and much less effective NeuroSky, et al) could be a huge change for researchers as they look to understand important research from a neuroscience perspective. One example would be the study at Stanford GSE on how walking stimulates creativity (Oppezzo and Schwartz, 2014). It would be useful to run this study again, with the participants wearing NIRS headsets to brain map the changes in creativity the study researchers were seeing.

Our research focus for 2015/2016 was Empathy. What is the role of empathy in games? Have players felt empathy in games? How could we use games that evoke empathy to bias downstream activities?

In January of 2015, Chris led some seniors at Castilleja School in a sprint to ‘Design For Surprise and Delight’ for their Global Week 2015.

Here are the notes from the design sprint exercise

60 mins total; need whiteboards and dry erase markers; or smooth surface and post-it notes and pens. The times under each section are for the entire section, including explanation, sharing and feedback. So don’t give participants that whole time. Cut it in half for ease (give them 5 mins out of a 10 min stint to design for #1, for example).

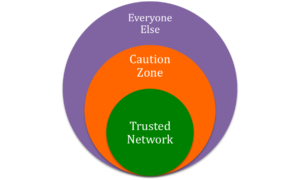

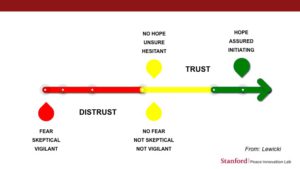

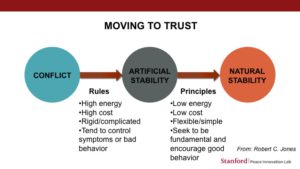

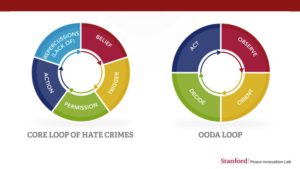

Our research focus for 2014/2105 was Trust. How do we lose trust? How do we most effectively gain trust once it has been lost?

Chris Bennett and Margarita Quihuis co-taught a pop-up course at the Stanford d.school called ‘Getting to Trust in Conflict Environments’, from which we created several useful frameworks and tools for our work in trust.

Trust Framework

Trusted Network/Comfort

Best friends and confidants: here you can truly be yourself

Caution Zone/Uncertainty

Friends of friends, neighbors, co-workers: here you tend to act a little nicer because there are repercussions for breaking trust. Facebook is a good example of this.

Everyone Else/Lack of Judgement

Everyone else in the world: here there tends to be no comebacks, so people tend to do whatever they want.

In order to reduce the size of the Caution Zone, you either need to move people you interact with towards the Trusted Network (trust) or the Everyone Else (anonymity).

But with the advent of social media, we increasingly find ourselves with a fourth position that occupies the space between the medium circle and the large circle. Where we sometimes speak as if we are in a Trusted Network, but we are actually in a space potentially more dangerous than the Caution Zone.

Danger Zone

Where we think we are speaking to a small group, but really our voice and options can be seen by a much wider group. And the repercussions can be large and sometimes life changing. Twitter is a good example of this.

This is a space where we are starting to see a lot of tribalism as millions of people are interacting together and causing friction of the edges of these disparate networks collide. Unfortunate side effects we have see are people being harassed, threatening or even losing jobs or their livelihood.