Designing for Difficult Subjects

Games are typically designed as entertainment to take us away from the “real world” and get us into what Johan Huizinga called The Magic Circle.

Temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart.

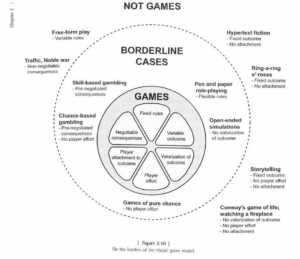

Jesper Juul has built on this with a wider definition of games and digital experiences in his book Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds.

So we can see that there are subtleties in the different kinds of experiences we can have; some are clearly games and some are clearly not games. And there are several shades of gray in between.

How do we use these learnings when we approach difficult subjects, especially in the classroom? We have ways to teaching and learning that are not games at all, or that are perhaps borderline cases. But what do games have to offer when looking at difficult subjects? Where do they falter? When do they add to the experience?

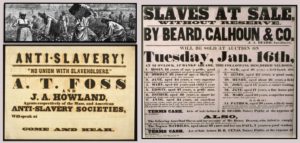

Let’s take a difficult subject like human slavery in history.

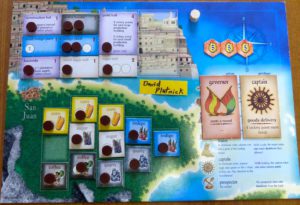

One of the most popular tabletop games of all time, Puerto Rico (2002) does not do this subject much justice. Sam Desitoff notes that the game:

…takes place on the titular Caribbean island during the 15th century. Players assume the roles of leaders of the developing export giant, and send workers to tend to the plantations and processing buildings. The game refers to these workers, who are packed on board a ship and sent to the island, as “colonists,” but examination of the game, as well as the history of the island, pegs them squarely as slaves.

Here, the makers of Puerto Rico chose to sweep this unsavory aspect of history under the rug and not deal with it in their game. Which certainly makes the game more approachable for a casual audience, which perhaps was their intent. But it also does not make it a game that is helpful at all for calling attention to the difficult subject and dealing with it in the open.

A much better job is done by Freedom: The Underground Railroad (2012). The publisher (Academy Games) website describes the game:

Freedom is a card-driven, cooperative game for one to four players in which the group is working for the abolitionist movement to help bring an end to slavery in the United States. The players use a combination of cards, which feature figures and events spanning from Early Independence until the Civil War, along with action tokens and the benefits of their role to impact the game.

Players need to strike the right balance between freeing slaves from plantations in the south and raising funds which are desperately needed to allow the group to continue their abolitionist activities as well as strengthen the cause.

The goal is not easy and in addition to people and events that can have a negative impact on the group’s progress, there are also slave catchers roaming the board, reacting to the movements of the slaves on the board and hoping to catch the runaway slaves and send them back to the plantations.

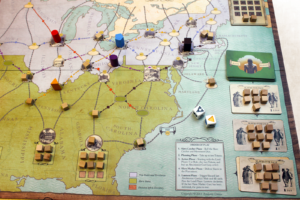

The board for this game is cleverly broken up into two halves which have two very different game mechanics.

The left side of the board shows the Abolitionist game, with cards and tokens to represent game events like the Dred Scott case.

The right side of the board shows the paths available to escaping slaves who are trying to leave the South. But it also shows the non-player Slave Catchers (see How Do You Create Paper AI?) who are trying to find them and return them to their owners. The designer Brian Mayer has done a wonderful user experience job literally portraying the Slave Catcher tokens as much taller than the small slave tokens they are trying to capture. Playing the game, the back and forth unstoppable movement of these Slave Catchers can feel quite ominous.

Freedom: The Underground Railroad deals with a difficult subject in a sensitive way. But it also does well by mixing the mechanics of both the political and economic struggle (the Abolitionist game) with the real life consequences of slaves trying to escape (the Slave Catchers game).

Unlike Puerto Rico, which tries to model a portion of history while ignoring the most difficult part of it, Freedom: The Underground Railroad takes ahold of this subject and makes it the core of the gameplay.

Since Freedom: The Underground Railroad is a cooperative game, no one is forced to play the odious slave holders or Slave Catchers. Far from it, the players really need to work together to achieve the dual goals of getting the most slaves possible over the Canadian border, and to try and end legal slavery in America.

Freedom: The Underground Railroad puts the concept of ‘human beings as currency’ front and center in the gameplay. You can’t get away from it, and much of the tension in the game is around keeping the escaped slaves from being recaptured.

One could make the argument that sitting around a board and moving wooden pieces that represent human beings running literally for their lives is a form of misery tourism, but I would not agree with that. While human slavery still remains a current crisis around the world, this game is looking at a specific period in time, much like reading a history book with more context and with the important addition of player agency.

And even though the game was not designed as a serious game or as an educational game, does it still have something to teach us? I would say that it does.

Even an initial setup of the game was instructive to me. I have studied the subject in school, but assumed that slaves were relatively safe once they left the South and made it to a Northern state. But the game clearly states that these slaves are not at all safe until they cross the Canadian border and are out of reach from the Slave Catchers roaming the Northern States in search of rewards.

This game can also be played solitaire, for those who wish to explore the subject matter by themselves.

Freedom: The Underground Railroad is a well-researched and thought out game, and it would be quite appropriate for any classroom or setting where this portion of history is being taught and analyzed.

More recently, Hollandspiele published a game by designer Amabel Holland called This Guilty Land (2018).

The publisher website notes that the game:

…is about the political struggle over slavery in the decades leading up to the American Civil War. Its central premise is that the war was the only way to achieve abolition: the slave states never would have willingly given up the practice, nor would it have worked itself out at some point down the road. This is a story of how the systems that democracies use to solve problems – debate and legislation – utterly failed in the face of an undeniable moral evil, of how that evil was defended by those systems, and of how calls for compromise only strengthened it and delayed the reckoning that had to come.

In this game, each player acts on behalf of an abstract idea – Justice and Oppression – with one player working for abolition and the other working against it. It seeks to treat the subject matter with sensitivity and respect. There is no piece that represents a human being – no action that replicates the horrors and the lived experience of slavery. Instead, this is about the framework that allowed that evil to exist, and the moral cowardice that enabled it to continue to exist.

The designer has taken the topic of slavery, and noted its sensitivity quite directly in the gameplay. Instead of modeling the mechanics of enslaved human beings who are trying to escape, and those who are trying to recapture them, the game concentrates on the concept of abolition and whether it should prevail.

In fact, the designer has written extensively about the game as being about the politics of slavery.

The publisher has also noted the difficult subject matter by only offering the game from their website, and not at retailers. And the game will not be officially featured at tabletop game conventions, although fans of the game will likely bring it to share with other players. This Guilty Land is a two player game, but like Freedom: The Underground Railroad, it also has high suitability for solitaire play.

Another part of the game that struck me was how it was trying to model the struggle for hearts and minds, which the designer noted was taken from Mark Herman’s GMT game Washington’s War (2010). So the game is about people; but not simply about the people being affected by slavery laws. It is also about the people who have agency, whether through voting or other means, to change these laws.

In talking and thinking about the atrocities of the era and how they are represented in This Guilty Land, the designer says that

And, like the question of how comfortable one is playing the game and playing Oppression, it’s a question with a very personal answer that’s going to be different for every player. If the game succeeds in asking these question at all, it does so by keeping the two players at a remove. Instead of asking the players to be someone else, it asks them to be themselves, and to look at this little paper time machine, to see how the pieces interact, and to draw their own conclusions.

So the design intention is that the difficult subject matter in the game is experienced at an arms length. Not to minimize or trivialize it, but perhaps to help drive personal reflection.

Since the 1960s, the vast majority of historical wargames have used cardboard counters with color schemes, numbers and graphics that are recognizable to experienced players. This creates a clear connection between the counter being moved on the board and the (usual) military unit that it represents.

But more recently, some games (like GMT Games’ Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001-?) have eschewed this for a combination of abstract wooden pieces to represent factions, powers or units on the board. The designer, Volko Runhke, has noted in an interview for another one of his games that using wooden pieces keeps the game mechanics simpler since “I can’t associate much information with any given unit type, only what is easily remembered from seeing the shape of the piece”.

Runhke continues, “With regard to immersion, the use of wood helps me because I can better envision through three-dimensional shapes in appropriate colors the groups of men arrayed on a field than I can with flat counters bearing numbers and images of a single soldier or two each.”

So how is the representation of individuals or groups in a game affected by the pieces that are used to represent them? Do we have more or less empathy for someone being portrayed in a game if they are a realistic 3D miniature or an beautifully painted card rather than a wooden block? And is that potential empathy necessary for understanding any difficult lessons around a game? These are good questions to think about as we look at and play these games.

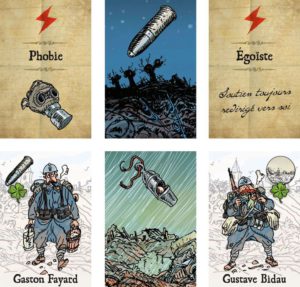

The Grizzled (2015) is a collaborative card game about the horrors of surviving trench warfare in WW1 where the players all win or lose together. The design by Fabien Riffaud and Juan Rodriguez is quite clever. But the artwork by Tignous is nothing short of breathtaking. Clearly the comic-style artwork on the cards makes the game of this subject matter more approachable.

The game is not about combat and the characters do not die. The game instead focuses on the mental strain that soldiers feel together. In fact, the manufacturer CMON is clear in their marketing that the game’s message is one of “peace and enduring friendship.”

Andrew Smith notes in his review of the game that

The first thing that caught my eye about The Grizzled was the theme. It’s unique and evocative. It’s a war game that doesn’t glamorize combat or even tactics, but is solely focused on the emotional impact of war on those who participate in it. This leads to a unique and immersive gameplay experience that doesn’t exist in many games. The theme comes through incredibly strong, especially for a card game with only a handful of cardboard components. The mechanics tie in exceptionally well and you feel sympathetic to the characters you are playing.

Can one learn about hope from a tabletop game about war? After several plays of The Grizzled I’m inclined to say “yes”. The game explores a difficult subject through a much different lens than we are used to, especially given the inherent agency of playing games.

So let’s step back now and see what lessons we can find about designing for difficult subjects. We are using analog tabletop games here, but the lessons apply to digital games and in fact many types of non-game experiences.

- What is sensitive about the difficult topic you want to design for? Get it out in the open so you can tackle it head on in your design and prototyping.

- Be intentional about what you want to explore. Players are looking for the designer to take the lead on what is important.

- Be clear about what you want to teach (if anything). Make sure your experience has the scaffolding to allow players to actually learn it.

- People will concentrate on the portion of the experience that has the most interesting moving pieces; make sure that is the core of your intended experience.

- Abstraction is a double-edged sword; make sure you know why you are abstracting a particular piece of your experience

- Players are not analytical robots; they are human and feel emotions. So what emotions do you want to explore?

By designing (or curating) experiences with care, we can move the study of difficult subjects from merely the passive realm of reading and watching videos and bring it into the interactive world that encourages shared exploration and discourse.